Convertible Notes Part 2: SAFE to KISS

In Part 1 of this series, I discussed the use-case for convertible notes and their key terms. In this second part, I’ll cover:

Other convertible instruments to raise capital, including a “simple agreement for future equity” (a SAFE). I’ll highlight key terms that are different to those in a conventional convertible loan agreement.

Priced equity round. A priced equity round is more complicated than convertible instruments because it requires a valuation exercise and more negotiations around future governance and documentation.

Other important considerations when issuing convertible notes. These include securities law, formal authorisation and pre-emptive rights considerations.

SAFE to KISS?

A SAFE is another commonly used convertible instrument. It shares many of the features of convertible notes, including their use cases and the key terms. For example, just like convertible loans, SAFEs are easier to negotiate and execute than a priced equity round (by deferring the valuation exercise), and they use a discount rate or a valuation cap or both.

The key difference between a SAFE and a convertible note is that a SAFE is not a loan. The investment amount does not earn any interest and there is no maturity date. The only instance where a SAFE becomes a repayable loan is when the company goes under. In this way, a SAFE is more friendly to the company and the founder team. (SAFEs were first issued by Y Combinator for this reason. SAFEs have recently turned into “post-money” SAFEs overseas. See more here).

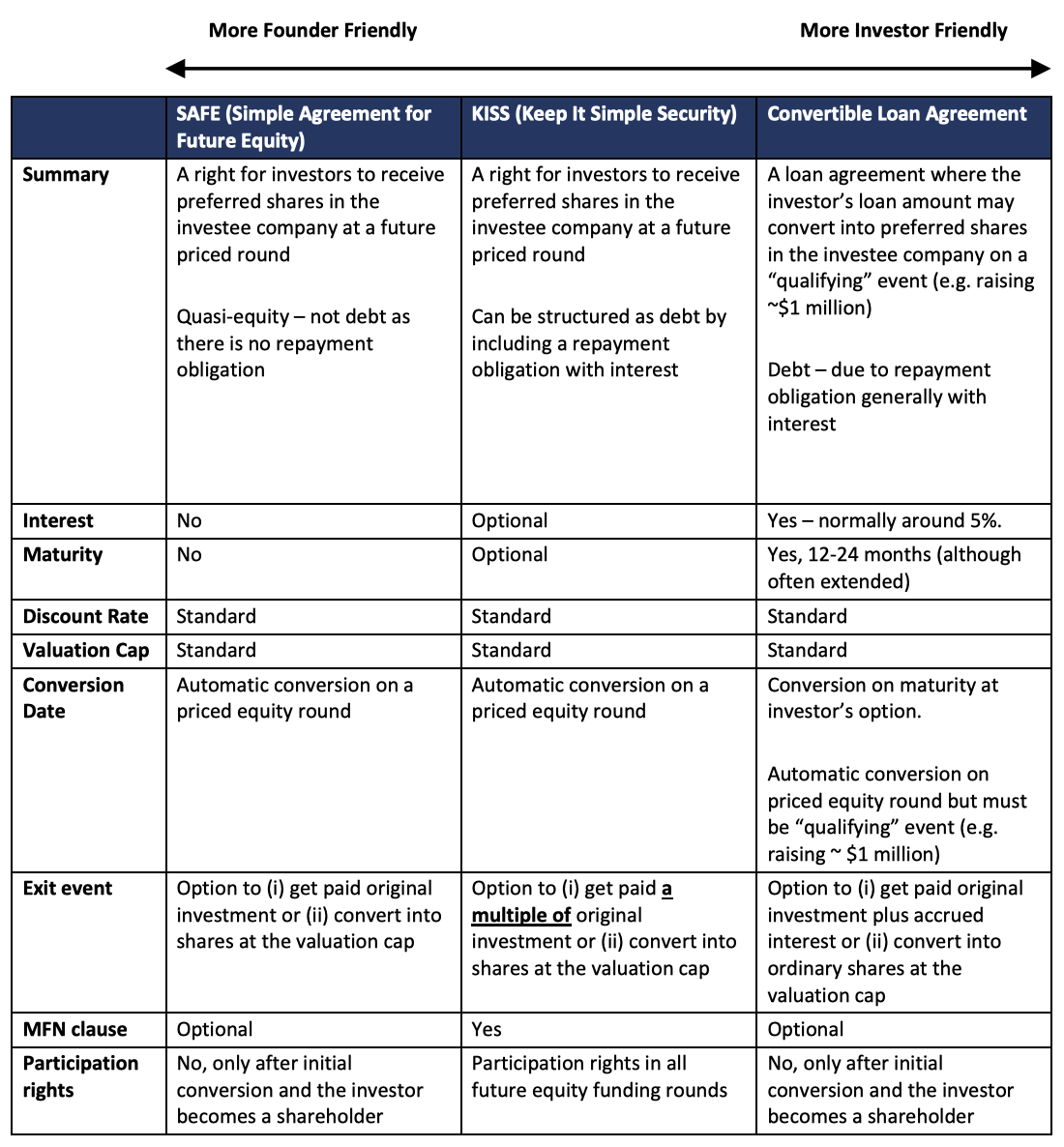

Another variation of a convertible instrument is a “keep it simple security” (KISS). Again, a KISS shares many of the features of convertible notes and SAFEs. Key differences are that a template KISS includes automatic participation rights in a company’s future equity rounds, a “most favoured nation” clause, and additional liquidation preference rights. These terms are investor friendly, so a KISS can be seen as a medium between a convertible note and a SAFE.

Here (and below) is a table comparing key terms of the different convertible instruments.

Regardless of the conventional names, all these convertible instruments are contracts between two parties. You can (and should) negotiate and tailor the agreement to suit your individual circumstances.

Priced equity rounds

The main form of capital raising – and the alternative to the convertible instruments – is a priced equity round. In a priced equity round:

Valuation – The company and participating investors agree on a valuation for the company. For startups, the valuation exercise mainly focuses on growth. These include growth around revenue, customer numbers and other financial trends and records. The agreed valuation is then expressed as “fully diluted”, so any convertible instruments are deemed to have been exercised into shares in the company and any shares reserved for employee stock plan have been issued. This helps investors to clearly see where their position is as investors in the company.

Share issuance – The company will issue actual shares in the company to participating investors. These shares typically have liquidation or dividend preferences over the existing shares. Being issued actual shares compares to raising money via convertible instruments, which are rights or options to future shares in the company.

Shareholders’ agreements – The legal documents are more heavily negotiated. The subscription agreement for the shares will include more detailed and fulsome representations and warranties from the company given in favour of the investors, and likely include additional conditions and pre-settlement obligations. The parties will also negotiate a shareholders’ agreement governing the relationship as between the shareholders and between the company and each shareholder. (See our article on shareholders’ agreement FAQ). These documents take longer time to negotiate and get right.

Governance changes – Following the investment, the investors will want to implement changes to improve and introduce a more formalised corporate governance. For example, they may introduce a board member with relevant industry experience or with skills to take the company to the next phase of its growth. The director may be an investor representative or an independent person, and can also be seen as providing oversight to protect the new shareholders’ investment. These governance matters need be agreed in writing, typically in the shareholders’ agreement.

Other legal stuff

There are also other considerations if you are raising capital:

Wholesale versus retail investors – Any form of capital raising needs to comply with the requirements of the Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013 (FMCA). Under the FMCA, the general rule is that you must make a “regulated offer” when raising capital. This requires disclosure of all material information concerning the company and other prescribed information such as the company's financial information, historical financial statements and key risks concerning the investment. These are set out in a ‘product disclosure statement’ and an accompanying registry entry. For startups, making a regulated offer is simply not possible from a cost and compliance point of view. You can get away with preparing a regulated offer if the offer is made only to selected investors to whom full disclosure is not required. Such investors include “close business associates”, “relatives” and “wholesale investors” (which itself has various subcategories).

Corporate authorisations – When issuing new shares or securities in the company, the board of the company (or the sole director, if it is a single director company) must resolve that the terms of and consideration for the issue are fair and reasonable to the existing shareholders. They also need to sign a director’s certificate with similar wording. These evidence that the board has considered the fairness of the share issue and the issue does not unfairly treat the existing shareholders (for example, by issuing new shares at a price that is less than what the existing shareholders have paid for their shares. However, doing so may be fair and reasonable under some circumstances so the board needs to consider and resolve that). Where new shares are being issued, the board can avoid the authorisation requirement by obtaining unanimous shareholders’ approval. However, this is not available where the company is issuing convertible instruments.

Pre-emptive rights – The other aspect of issuing new shares or securities is the pre-emptive rights. Before issuing new shares or securities, the board should consider whether existing shareholders have pre-emptive rights that apply to such issue. If so, they need to offer the new shares or securities to the existing shareholders or obtain their waiver of pre-emptive rights. The position for the company will be different depending on whether it has a constitution or existing shareholders’ agreement or other relevant terms of issue.

These are not a comprehensive list of key legal issues, and are matters that can be easily overlooked. If they are overlooked, then the board and the company would very likely be breaching one or more of their statutory obligations under the Companies Act or the FMCA with potentially serious consequences. Obviously, I’m conflicted in saying this, but do check with your legal advisor when planning or executing a capital raise to make sure you are not falling foul of them.

What next

If you have any questions about how you can use or negotiate a convertible note, please contact Josh Woo.

If you liked reading this content and want more, please subscribe here.

Disclaimer

This publication should not be construed as legal advice. It is necessarily brief and general in nature. Please seek professional advice before taking any action in relation to the matters discussed in this publication.